This is a resource about stones in King’s Lynn. It was inspired by the exhibition of work by the great Dutch artist herman de vries ‘on the stony path‘. Starting from his remarkable collections of stones, earth rubbings and assemblages, we looked afresh at stones all around us. We ranged through King’s Lynn and beyond in the landscape and the built environment.

In memory of Robin Stevenson

The late Robin Stevenson’s work is at the heart of this resource. Robin was a local geologist and former lecturer at the College of West Anglia. We are much indebted to him for so generously making his researches available.

King’s Lynn.

King’s Lynn sits on the banks of a major tidal river, the Great Ouse. It is just south of The Wash, and on the edge of the Fens. The nearest rocks suitable for building purposes lie several miles inland, to the east. Or we have to go north-east, or way over to the west in the limestone belts of Lincolnshire and Nottinghamshire. During medieval times, when the town was built, road transport was difficult and expensive. So cheaper transport was largely by water. This meant that good building stones were essentially inaccessible. However, despite this, the buildings of Lynn display a wide variety of materials, which illustrate the long and complex history of the town. The oldest buildings in any town belonged to either rich and powerful individuals, or organisations. The Church was the most important of these.

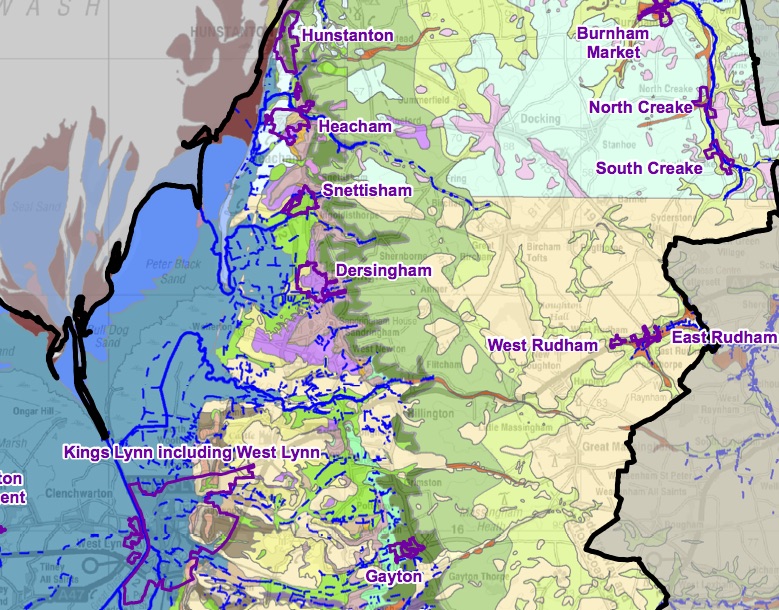

A geological and environmental resource

This resource introduces you to the main rock types you encounter, and to the buildings where you will find them. It will give you a flavour of how, when and why these rocks arrived in Lynn. We hope that it will help, you to interpret the history of buildings and their relationship with the wider environment. It will also take you further, in and beyond King’s Lynn, as you do your own exploring.

Early Stone buildings

Most buildings (including medieval churches), consist of a mixture of components and demand a variety of skills in their construction. Local, relatively unskilled labour, and cheap materials were sufficient to build the framework. However, skilled craftsmen applied the finishing touches with prestige quality materials. Most of the quality components would have been manufactured at specialist centres elsewhere and delivered as a set of ‘flat-pack’ components to be assembled on site.

The major medieval churches in the town: St Margaret’s Church, and St Nicholas’ Chapel are faced entirely in limestone. This high prestige stone needed to be imported as there is nothing of this quality available locally

Limestone

Limestone is a sedimentary rock consisting mostly of Calcium carbonate (CaCO3). Oolitic limestone is made up of small (sand sized) rounded grains (oolites). If it consists purely of oolites it may qualify as a freestone, which can be cut or carved in any direction. If, however, it is ‘contaminated’ with coarser shell fragments then it is a rag, or ragstone. These give the rock a distinct grain along which it tends to split,

Where the limestone came from? The only sort of limestone which

occurs in Norfolk is Chalk, which is usually very soft and so unsuitable for building major structures. The nearest sources of good quality limestone lay on the other side of the Fens, in Lincolnshire and Northants. From there it was brought in by barges traversing the numerous dykes, drains and rivers of the Fens. Good quality oolitic freestones came from a number of sites. However, the quarries around Barnack were the chief source for Ragstone. Although the dominant types of limestone come from Lincolnshire and Northants, other types can be seen in the church interiors.

King’s Lynn’s two great churches: St Margaret’s (the Minster) and St Nicholas’s chapel

It is worth noticing the different flood levels incised round the entrance to the Minster,. These are a reminder of Lynn’s position on the banks of a major tidal river. Inside the church, on the north (left hand) side note the distinctly leaning arch. This is a result of building on clay soils, which shrink and swell, as soil water levels change in response to drought or flooding. It is a hazardous enterprise.

The main body of both St Margaret’s and St Nicholas churches present a smooth ashlar finish. Both however, have significantly more elaborate carving present on the facades and porches. Ashlar is a surface of thin slabs of freestone which conceal a rubble interior. Inside the church the rubble is usually hidden beneath a mortar covering, or render.

St Nicholas Chapel, is a building of outstanding design for its late 14th-early 15th century date & of European importance. Probably the stones for the window tracery and the doorway would have been supplied direct and pre-cut from the quarry

The Trinity Guildhall

The Guildhall, which is situated very close to the Minster, is another example of a prestige building employing ‘quality’ stone. Again the chief materials are Lincolnshire limestones. But here limestone alternates with flint in a chequered pattern called ‘flushwork’. (see below another example at All Saints clerestory)

Flint is a hard black material found embedded within some layers of the Chalk. Suitable flint for flushwork, as on the Guildhall facade, does not occur anywhere round Lynn. So it had to be brought by barge, probably from further south in the county, from around Thetford or Brandon.

Ashlar, rubble, flushwork and reused stones at All Saints church

All Saints church is a revelation, as it shows the bare bones of church construction. Strip away the veneer of ashlar panels from the great churches, and this is probably what they would look like. It is like the rubble skeleton on which the smooth sophisticated exterior hangs. The upper walls of the clerestory are flush-work, which is flint alternating with cut ashlar stone in a checkerboard pattern

The Custom House

After the end of the Middle Ages, Lynn lost its position as one of the major ports in the UK. Despite this, it remained prosperous enough for many fine buildings to be erected. However, few new materials were employed but extensive reworking and reordering of older buildings took place. The main building material was brick and, to lesser extent, recycled limestone. Or Lincolnshire limestone might be specifically imported for prestige projects, like the Custom House of 1683.

Rubble

Stone has always been expensive and money has always been tight so, even early on, masons learned to practise economies. Chief amongst these was the use of rubble. As we have seen above, churches were only faced with cut stone on the outer layer. Beneath it was a much rougher construction of irregular rubble. Stone rubble was also used for extensive utilitarian structures, like town walls.

Rubble also had value. Around Lynn there were, until recently, no readily available sources of rubble. So it would have to have been imported, either deliberately or coincidentally. The main sources of rubble in King’s Lynn would have been either recycled from earlier buildings, or deliberately imported. This was probably otherwise waste material from the quarries producing higher quality stone.

Wyatt Street town wall and diverse rock collections

The town walls in Wyatt Street are a veritable collection of interesting imported stones. They probably all came in to the town as ballast in trading ships from the Baltic.

In medieval times Lynn was one of the major ports in England. It traded with its partners in the Hanseatic League, across most of northern and eastern Europe ( http://www.hanse.org/en/ ).

Ships coming into port without a load, were weighted down with ballast. This was stone, basically and this explains the import of some of the unusual stones we find in the walls. The ballast was then discharged before the ship was loaded and departed. And then it became useful rubble for building material.

Ballast

Ships coming into Lynn from distant ports may have picked up ballast materials from their local beaches. These provide very interesting historical evidence of travel and trade. In some cases these materials were sufficiently distinctive as to be able to be traced back to specific regions. Some of the rocks in the town walls, for instance, came from Norway, southern Sweden and the eastern Baltic. They include sedimentary rocks such as sandstones as well as igneous and metamorphic rocks.

Igneous Rocks. Granite / gabbro / basalt/ porphyritic textures / vesicular basalt

These rocks originate at depth in the crust, as liquid magmas. They can be very variable both in texture, composition and colour. Igneous rocks do not occur naturally in Norfolk but are frequent components of ballast. They probably originated in the Eastern Baltic, as well as having been introduced deliberately as building materials.

Basalt

Amygdaloidal granite

Rapakivi granite

Gabbro

Sedimentary rocks. Mudstones and shales / sands / grits / gravels / oolitic lsts / shelly lsts / coal / rocksalt / gypsum

Familiar examples of sedimentary rocks include muds, sands, gravels and limestones. They consist of fragments of pre-existing rocks, broken down by weathering and then transported and re-deposited. Transport may have been as physical particles (e.g. sands). Alternatively, the material may have been transported as chemical solutions, which subsequently became re-deposited. This could have been either as a result of chemical or biological processes. As a result of their methods of transportation and deposition sedimentary rocks very frequently show signs of layering or bedding.

Hornblende-mica Schist

Shelly Barnack Rag

Metamorphic rocks. Slate / schist / gneiss

Like the igneous rocks these metamorphic rocks often originate at depth in the crust. They form when pre-existing sedimentary or igneous rock are subjected to high temperatures and pressures, as a result of deep burial and/or earth movements. If heated enough these materials may melt completely, and re-enter the magma pool. However, before that occurs the texture of the quasi-melted rock may result in the formation of new, larger, minerals, even though traces of the original sedimentary bedding may survive.

Coarse Gniess

Porphyritic Andesite

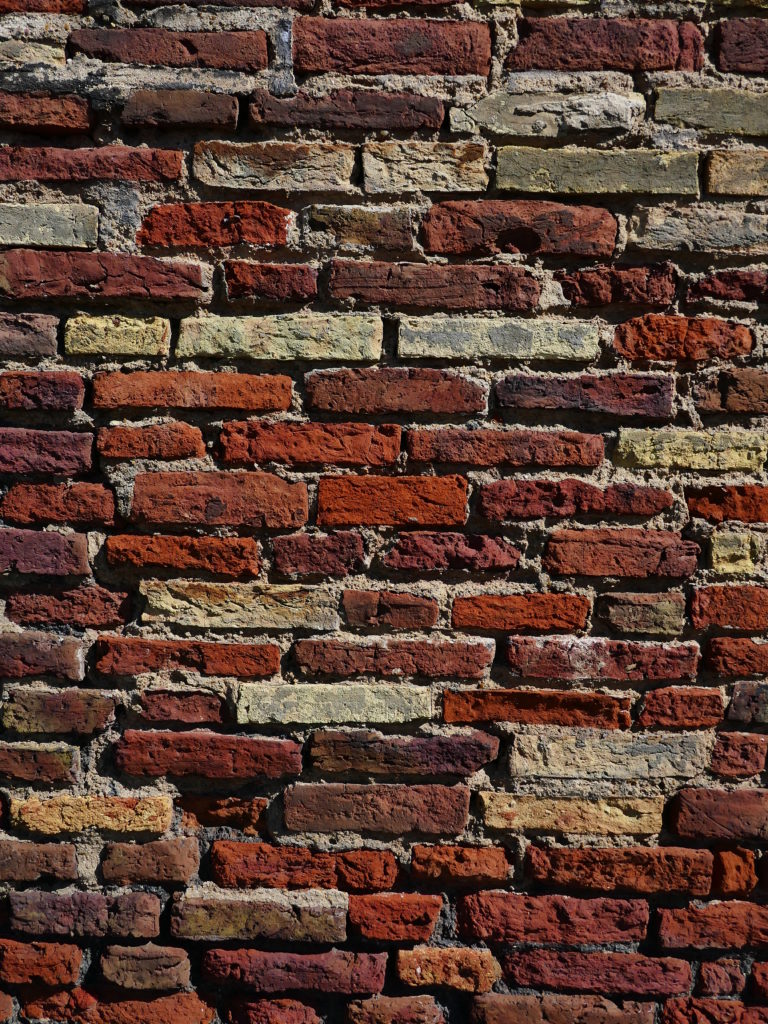

Brick building

Brick are made of clay formed into rectangular shapes and then baked in a kiln. They emerge hard and durable.

In early periods, ordinary people would mostly have lived in huts made of wattle and daub . In effect this was mud, plastered onto a framework of wooden poles. However, as the town and its people prospered more sophisticated building materials would gradually have become available. Of these, stone, because of its durability and aesthetic qualities remained pre-eminent. Brick was the dominant material available to the less well-off.

The quality of the raw materials available was clearly variable, as were the skills of the brick makers. This accounts for the huge range in colour and textures seen.

Although the Romans knew how to make bricks and tiles this technology disappeared in England for a few hundred years after they left. However bricks were probably introduced into East Anglia from the Low Countries as early as the 12th century. At this point the wealthy would have been able to build more substantial timber-framed houses. Bricks filled in the gaps between the timbers of the main frame. It is the construction method we see today in Hampton Court .

Half Timbering.

There are only a few examples of half-timbered houses left in Lynn. The Lattice House, in Chapel Lane shows the brickwork very clearly.

From the 16th to the 19th centuries, until the advent of the railways, Lynn remained relatively prosperous. But its overall importance declined somewhat. Its main trade continued to be across the North Sea. Other ports on the west coast became more prosperous on the basis of the Atlantic trade.

Improvements in transport overland were slow and fitful, so it remained difficult to utilise local materials other than brick. However, rich merchants expressed their status by the simple expedient of building bigger and better brick houses for themselves. In many cases these were built around and over the shells of older buildings. These may have been based on rubble (including ballast) as well as timber frames.

Red Mount Chapel

The Red Mount Chapel, (situated in The Walks), is an interesting example of an early (1485) brick built structure. It also incorporates quite a lot of oolitic limestone on the quoins and around the windows. This is what one might expect of an important ecclesiastical building.

Gates and smart town buildings

The South Gate of the town, and the Whitefriars Gate are also built from brick, rather than rubble. Like All Saints church, they both have limestone detailing at the corners.

In a poor stone area, where muds and clays were readily available, the technology of brick making quickly took root. In the absence of any common standards they varied considerably in size and shape. Although they were all (more-or-less) of a size which would fit comfortably into a human hand.

Brick Bonds.

Bricks are formed in rectangular blocks, in moulds. The long side is known as a stretcher, and the short end as a header. There are a number of different ways in which bricks can be laid relative to each other. These are called ‘bonds’ Although the primary purpose of the bond is to strengthen the structure of the wall, aesthetic considerations are also involved. So brick bonds often form patterns, especially if different coloured bricks are available. In older buildings the commonest bond pattern seen is the English Bond. Flemish Bond was introduced in the c17.

Tiles

At early dates, most ordinary buildings, (other than churches and other ecclesiastical structures), would have been either thatched with reeds or covered by wooden shingles. These were very vulnerable to fire risk and were later replaced with tiles. No such buildings remain in the town.

Tiles appear to have come into use before bricks (whence the common surname Tyler). The earliest tiles were flat, like shingles. They are made from the same materials as bricks, and by the same process.

Later uses of stone

The arrival of the railway to King’s Lynn, in the 1840s, meant that transport costs were drastically reduced. This allowed the importation of stone from a much wider field, and ironically also from closer at hand. The development of turnpike roads had improved communications in general. However, the fact that they were toll roads meant that they were probably not that much used for the transport of high bulk, low cost materials such as stone. Stone was still mainly transported cheaply by river. So, even though it was a relatively local stone, Carr Stone, which was not on a river route, did not appear in the town until after the mid-19th century.

Local stones and materials

Carr Stone

The most widely used local stones were from the two Lower Cretaceous units the Dersingham Beds and the Carstone. These two separate geological units yielded somewhat similar materials known respectively as Small Carr and (simply) Carr or Carstone.

Carstone: this is a generally coarse foxy brown material which can occur in quite big blocks. Occasionally it is traversed by thinner, darker, seams of slightly better cemented material; it may also contain occasional small pebbles of white quartz.

Small Carr: This is derived from the slightly older Dersingham Beds. It is usually somewhat finer grained, and darker in colour than the big Carr. It usually comes in thin slabs.

The Town Library (London Road) is Victorian, and constructed from local Carstone, with interesting brick and terracotta detailing. Although there are good outcrops of Carstone not far away, they were not exploited to any significant degree until improved transport links (and its use in Sandringham House), made it much more fashionable.

Because it was abundant and cheap Carstone quickly became the restoration material of choice. It is, for instance, an extremely conspicuous component in the Greyfriars Tower. Ironstone may well have been a significant component of the original rubble fill. However, Carstone was used for later repair work simply because ironstone was no longer readily available.

Because Carstone was the main material used in the royal residence of Sandringham House, this undoubtedly raised its profile. As a result it became much more fashionable.

The Greyfriars Tower (St. James’ Street) is a remnant of an original Franciscan friary. The rest of it’s stone was presumably used as a quarry following the Reformation, its stone being recycled elsewhere in the town. It incorporates quite a lot of ballast materials but also contains much carstone. However, the latter may have been introduced as a repair material much later. Again, limestone is used on the quoins and for detailing.

Ironstone.

Although this is a local stone there are very few examples of its use in Lynn. you can, however, see it in the exterior walls of the cottages on the north side of Priory Lane. It has been much confused with Carstone. However, it is a geologically much younger post-glacial deposit. It consists of coarse sand and gravel material, heavily cemented by dark brown iron oxides.

Elsewhere in the county it is much commoner. It seems to be especially associated with Saxon buildings where it was probably encountered in the course of drainage works. It occurs as isolated blocks of rubble in Priory Lane, blocks which may have been recycled from earlier Saxon buildings. There are very few places where you are able to see Ironstone in situ nowadays. The suspicion is that a lot of the Carstone seen in structures such as the Greyfriars Tower is only there because Ironstone is no longer available for repair work.

Back to art

German artist Sibylle Eimermacher made a wonderful film in 2016 about the gneiss stones on the eastern coast of Finland. It was shown alongside herman de vries, ‘on the stony path’. The subtle variety of the stones captivated her and she spent weeks exploring their detail. http://www.sibsite.eu/