by Veronica Sekules

We need to transform our attitudes to waste . It needs to be rehabilitated. Not as an inconvenience, nor as a disgusting embarrassment, nor even as a potentially random commercial resource. Waste needs to be recognised with its potential for longevity and status-change as art and heritage. Categories matter. A shift in attitudes can potentially turn what is currently a burden into an asset. That is the way waste can end. It is only then that it will be play its part as a positive resource in counteracting the extractivism which has contributed so significantly to the effects of climate change.

This article is a short introduction to a longer version, discussing Art as Waste and Heritage, published by Mark Goldthorpe in Climate Cultures, creative conversations for the Anthropocene, – do subscribe to it and then you can read the long version and everything else he circulates in his wonderful publication.

Here, this is really a series of thoughts following from our exhibition from March – July 2023, The Art of Waste. The exhibition featured the work of eight artists, all of whom were in different ways also musing on the subject of waste, bringing creative responses to it into their practice. GroundWork Gallery itself lives in a building saved from waste, a converted little 1930s warehouse, which the planners and heritage officials at first wanted demolished to make way ‘for something more suitable’, as they put it. Of course we were never going to remove the last 1930s industrial building from the centre of town, so stood up to them and converted it.

The gallery, as regulars will know very well, is dedicated to the environment and to the role of art and artists in helping us to rethink aspects of it, and to understand and treat it better. This is vitally urgent now in our times of crisis. I believe art can carry a powerful message or ‘voice’ to a much wider world than the narrow confines of the conventional art world. Together with our diverse communities, we need to communicate art’s innovative messages across to wider publics, other disciplines and contingent professions. That is how we begin to achieve change through bursts of inspiration, sudden insights, and above all through widening influence.

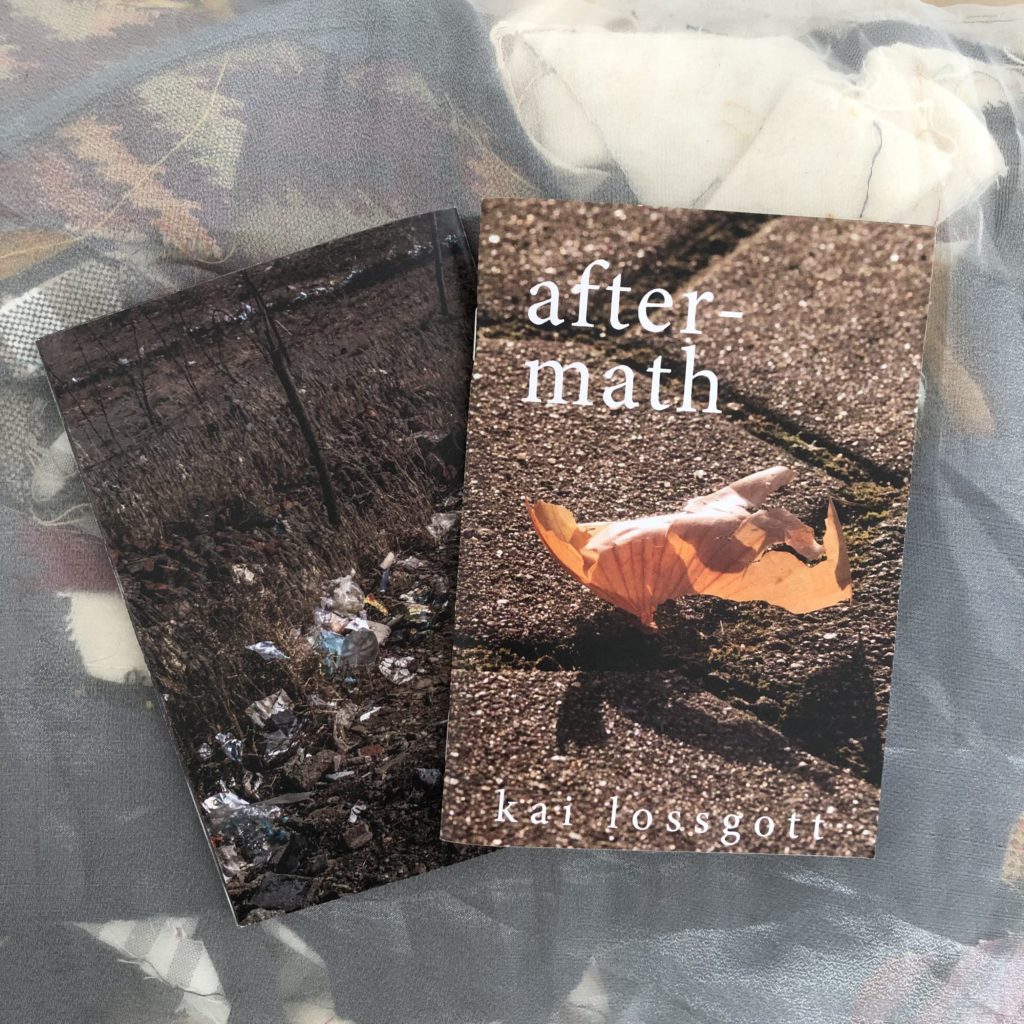

Left: Liz Elton, compost print; Middle, Jeremy Butler: Landskip, Garden of Eden; Right, Kai Lossgott, Aftermath – a poetic book about landfill

Environmentalists hate waste

Environmentalists hate waste. This is the starting point for all the work I am discussing, as artists hate waste too, and many of them are trying to find creative solutions to the way we think about it and literally view it. However, this article proposes that we rethink the category of waste to include formally, not just its relationship with art, but with heritage, and about the potential status of waste as both art and heritage. The re-categorising and the status-change involved will play its part in counteracting the extractivism which has contributed so significantly to the effects of climate change.

Each of the artists in the Art of Waste used waste materials as creative resources, making use of surplus materials, implementing circular economies, being very economical in leaving nothing behind. As well as inventive practical strategies, the artists excelled in changing the status of waste, from that of detritus and ephemera, to be something precious and valued. Just a couple of examples outline the resources and methods the artists used. Jeremy Butler made his bird’s eye view reliefs of landfill sites and waste skips with such a meticulous and tender attention to detail, with an edge of humour, they get us absolutely primed for rethinking their value as being beyond repositories for unpleasantly smelling trash, more as potential havens for treasure. Liz Elton’s huge billowing hangings made from draped bioplastic food packaging dyed and painted with waste food and earth pigment, redefine what a majestic wall tapestry can be. On a much smaller scale Lizzie Kimbley, a proponent of a circular economy for her art, uses only waste thread and cloth, tiny stitches, exact measurements, to create new textiles which have absolute precision, in contrast with the expectation that waste cloth otherwise might conjure up. (see Appendix for further brief details about the artists)

Left: Lizzie Kimbley, ‘No Away’ from waste linens; Right: Jan Eric Visser, Untitled (from Durer 1492) made from household discarded inorganic waste & ends of computer inks

The immediate impact from the exhibition was measurable to a degree from the visitor’s book comments. Responding to the exhibition, many visitors remarked that it was ‘inspiring, relevant and thought-provoking’. However, it was also ‘unsettling’,‘bringing new perspectives on waste’, ‘makes you think about waste, awe inspiring’, Some were moved to more action ‘Interesting ideas, we need to reach out to everyone’, ‘ WE NEED TO DO MORE’, ‘ much needed’, ’love being eco’, ‘we waste so much’, ‘educational and makes us aware of our industry and pollution’, ‘who knew waste could be so useful – makes you think’, ‘feels very dystopian’, ‘compulsory viewing for all politicians and their influencers’. One of the youngest visitors wrote: ‘Makes you think about waste. Awe inspiring’. The positive immediate impact was gratifying but just a beginning. It showed to an extent the desire of people to be receptive to new creative ideas and how these can stimulate our societal needs to change. However beyond the specificity of the timescale and place of the exhibition, there needs to be whole lot more thinking about how we can mobilise the creativity of artists and these kinds of responses to it. Where does it get us and where can it lead? What does that kind of power enable and what and with whom can it both connect with, and lead to?

Left: Henry/Bragg, still from The Surrey Hills, of Nigel landscaping a landfill site. Right: Mpumelelo Buthelezi, Johnny in Soweto loading a waste truck from waste saved from landfill.

We need a paradigm shift for waste

Recent publications about waste have been proposing various paradigm shifts which involve a change in consumer habits, moving away from a throw-away economy of short-term use and of things ‘becoming useless’, to one of waste as asset creation. Some would argue that waste as an entity ought to be entirely avoidable, or even non-existent, providing that materials, foods and resources are used by people with greater economy and efficiency. Within the framework of Discard Studies, the entire concept of waste is open to interrogation, from all points of view including the wider societal and economic implications of the way it is handled to critical analysis of normative values that have created and interpreted it in the first place. In sympathy with that interrogative framework, I would add that a paradigm shift for the way waste is categorised will help us all to prioritise what and how and why we save the stuff of the earth. Increasingly, students of waste, entrepreneurs repurposing it and artists creating with it, are recognising that waste needs to be rehabilitated as a transformative resource, not with the shifting values of random commerce or the vilification applied to detritus.

Above: Eugene Macki installation from waste furniture, The Art of Waste at GroundWork, 2023

In setting the framework for further discussion, the longer version of this article raises in outline some of the issues in the definition of heritage and of the potential for waste as heritage. It touches on some of the enormous complexities of the subject of waste, such as how and where is waste accumulated and what are the problems of distribution. I touch on the subject of who the various categories of ‘we’ are who are creating the problems. Then taking a lead from a series of artists’ projects I take a look at two specific contentious waste subjects in more detail: land-fill sites and plastics, and how they might be faced afresh. The way these subjects have been tackled by artists, writers and archaeologists hold the key to the category shifts we need from dumps and surpluses to treasure, from waste and trash to art and heritage.

Left: Liz Elton with Cornstarch hanging painted with kitchen waste. Right, George Nuku with Plastic Ocean installation, Rouen

The innovative ways in which artists are using waste materials can lead the way to a shift in values, potentially turning what is currently a burden into a heritage asset. Categories of definition matter and both art and heritage are relevant. Waste’s role as heritage specifically, needs to be brought into focus more, in order that we give greater value and the right kind of longevity to all the earth’s material and how we are using it. Shifting values affect attitudes. Applied at scale, that is one way the idea of waste as bulk mess and detritus can end. Instead, if surpluses, left-overs and spent materials are sorted not only by re-use potential, but as categories of art and heritage, this re-categorising can turn a negative into a positive asset and environmental benefits and the economic consequences can follow.