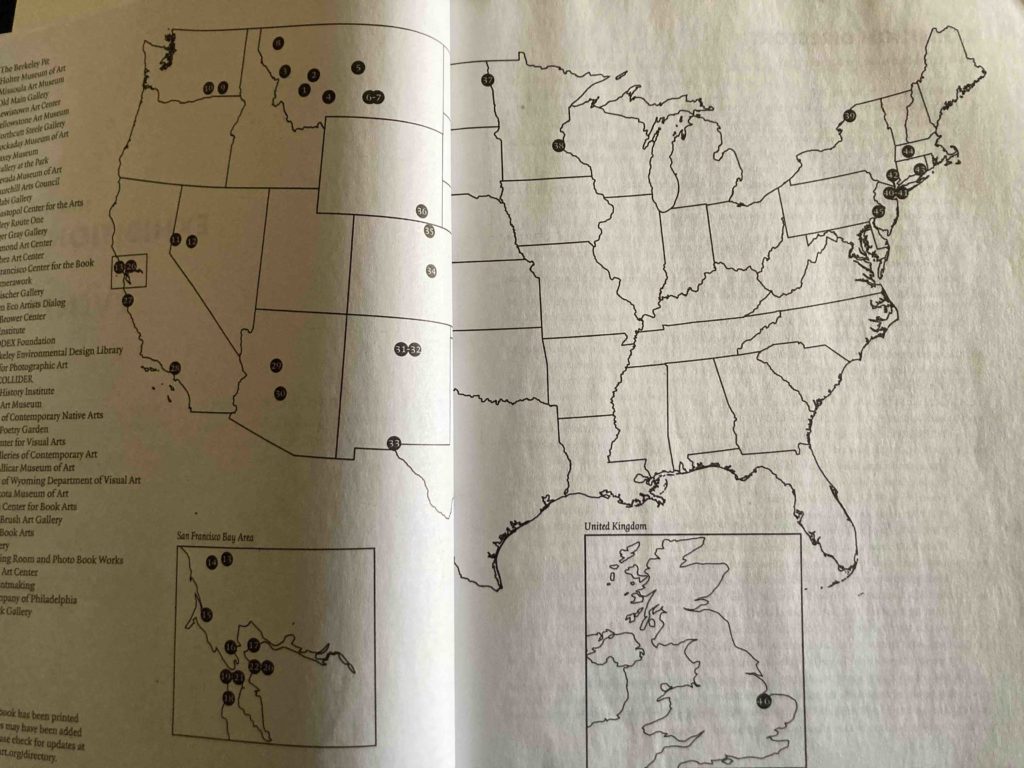

Linked to: Extraction: Art on the Edge of the Abyss

GroundWork Gallery’s Extraction Project Residencies

GroundWork Gallery’s extraction project residencies will involve artists and partnerships working sustainably with flint, chalk, carr stone and silica sand. We are delighted to be part of the Extraction Art on the Edge of the Abyss programme.

It is very much our mission to ensure that art and artists play a part in increasing our care for the environment. The impact of art starts with a deeper insight and understanding. Then hopefully that leads to inspiration and influence.

The aim of our Extraction project is to provide a counterpart to the dramatic images of the vast mines and tar sands of the United States (see our blog post which shows some examples). We are fortunate in the UK in having a planning system which on the whole is pretty draconian and does not allow real devastation to the environment. But it requires constant vigilance, and protest, as we are experiencing currently with a proposed new coal mine development in Cumbria. It has had provisional approval even though its development runs totally counter to the Government’s stated aims for reduction of carbon emissions.

We cannot afford to be complacent. We cannot entirely trust the system. As Michael Traynor’s Afterword to the Extraction Art on the Edge of the Abyss book says:

Professional disciplines such as science, engineering, law, economics, public policy, and journalism are necessary but not sufficient to counter unsustainable extraction, environmental injustice, greed and ignorance.

Michael Traynor

The artists in residence

Kaitlin Ferguson 9-22 August

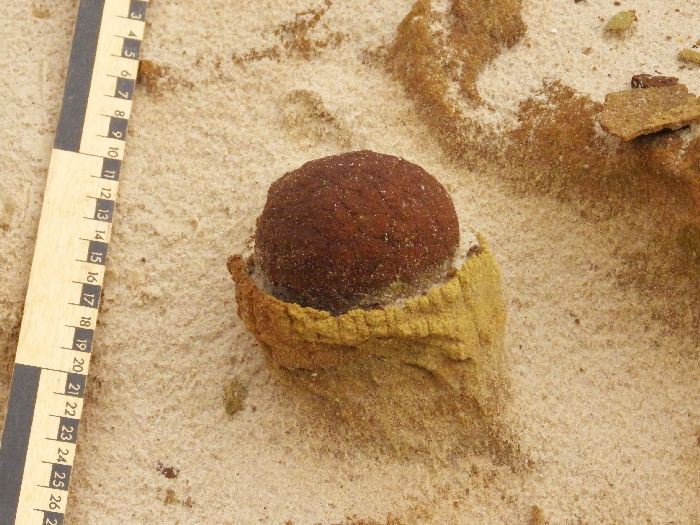

My research focus during the residency will on flint and chalk, and to understand the scale and complexities of the consequences of extraction of these materials on local landscapes. Seeking to explore what markers will be left in the strata of the earth in this area by this industry, as well as within the wider context of the Anthropocene.

I will also be furthering my ongoing research into the formation of chalk in this area, looking across millennia at the elements which caused its formation, seeking to develop artistic entry points to better understand this material across the parameters of scale and deep time.

Furthermore, I am keen to explore the waste and by-products which are produced through these industries and whether these can provide the possibility to be harnessed in the production of pigments and bio-materials.

Shaun Fraser 23 August – 6 Sept

During my time undertaken with the ‘Extraction’ residency I plan to engage with the issue of mining and silica removal in the Norfolk locality.

Silica is a material which I have previous experience with as it is one of the key materials utilised in glass casting processes.What I hope to do during my research is to consider the role that this extraction plays within the region and to also look at what scars are left upon the landscape through the process of extraction. In previous work I have looked at the notion of landscape as a palimpsest – revealing markings and intimations to past episodes, being able to be read as a parchment with layer upon layer of narrative. This is a recurring concern of mine and I hope to be able to delve into this within the Norfolk context.

Rebecca Faulkner 6 – 18 Sept

I already come to the residency with a focus on sand mining and extraction, but whilst this has mainly focused on London the AER opportunity would allow me to return and work in my native Norfolk. Through a partnership with GroundWork I would be able to understand and reveal the exploitative process of sand-mining, but also of flint, chalk, and carr stone. I grew up on these very beaches, which not only are subject to coastal erosion but beach replenishment schemes which only act as a bandaid to Norfolk’s declining coastline. A circular process of offshore sand-dredging for construction leads to beaches vanishing and further dredging for beach nourishment only serves to perpetuate this, not to mention the suffocation of marine and beach life.

Like Minds Norfolk

Like Minds Norfolk joined our project with their own investigations of some very special quarry sites. They focused on Blackborough End – a site formerly concentrating on aggregates and which stopped excavating some 15 years ago. It is now being restored into a beautiful and biodiverse landscape, with lake, woods and ravines where the quarried faces were.

Ian Brownlie was the artist who guided and worked with them. He recorded their results and also made a series of works of his own in drawing and film.

Keeping an eye on extraction projects

So the more we keep an eye on any extraction process, the better.

Michael Traynor, like us makes the case strongly for the involvement of artists and all creative people in showing the way to a better and more sustainable environment. But for real change to happen, there has to be opportunity for greater dialogues to emerge with viewers as well. Participants who then can become co-creators of a project. We need wider involvement beyond the small core of creativity at the centre.

Ideally this involves different disciplines and realms of expertise. Consequently, all GroundWork projects are accompanied by campaigning in partnership with others. Creating and showing art is the beginning of a process of engagement. This approach and process has informed the planning of our forthcoming Extraction projects.

Extraction of flint, chalk, carr stone and silica sand

GroundWork’s Extraction: Art on the Edge of the Abyss project will concentrate on links between extraction, environmental management and applications in the built environment. It will explore the distribution and quarrying of flint, chalk, carr stone and silica sand.

We will look at: a) the heritage b) technology c) industry d) impact on the landscape e) implications for the environment. Art will be central to this. We will invite artists and writers to research the entire field, or their chosen aspect of it. They will make work in response, which will we will show at the gallery . Our partners and collaborators will also be guiding our approaches in various ways, over the next two summers, 2021-2022.

The work of the artists

We are aiming to involve at least four artists and writers over two years. We will introduce them as they join the project.

Depending on their specialisms, the artists will take photos and film, make sketches, take 3D impressions, make walks. Each artist will make a body of work, which can be interim works to show their processes.

Together we will pull together the research materials to create documentary records. There will be one major interdisciplinary public live + online conference event per year.

Tim Holt Wilson, Norfolk Geodiversity partnership

These extractive industries produce raw materials to feed an industrial economy and thereby generate capital and indirectly also contribute to the exponential growth in the Anthropocene project of transforming the Earth into ‘second nature’ – a state of the world in which Earth’s life-support systems conditioned by natural, biological processes are replaced by humanly-conditioned, artificial ones.

Our partners and collaborators

We are delighted to be receiving a small project grant from the Norfolk Coast Partnership. We look forward to working with them, as they give us further guidance. The Norfolk Geodiversity Partnership is another principal partner and has already contributed significantly.

We will be interviewing some of the quarry owners and their workers. We will also consult professionals involved in the use and application of the stone, for example, in the chemical industries and construction trades.

The Restoration Trust will also be joining us during their ‘Like Minds Norfolk’ programme.

Through all these perspectives we will gain a picture of the management of the landscape, their environmental ethics and how people see the bigger geological picture.

The background and geology

Tim Holt Wilson, Norfolk Geodiversity Partnership

“Over past centuries the landscape became pockmarked by small quarries taking minerals for local use. In most cases these have fallen back to nature and are now wildlife refuges. Since the early 20th century, large quarries have developed in the sandrocks of the King’s Lynn area, as at Bawsey, Leziate and Middleton. They serve national and international markets, and have had a correspondingly large visual impact on the landscape, being visible even from space! While the environmental impacts of the minerals industry are carefully controlled by the planning system, it is evident that quarrying destroys finite natural landforms – in this case part of a landscape which has taken over 400,000 years to develop since the end of the Anglian glaciation.’

Sustainable extraction management

It is in all our interests to ensure that the business of quarrying is sustainably managed. The coastal area is an AONB – an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. As such, it has certain protection, but is still vulnerable to unwelcome development. We feel strongly, alongside our American counterparts that art projects can raise awareness as a prelude to action. This is the reason why we are building strong partnerships around each of the Extraction projects we will undertake.

Disused extraction sites can cause enormous problems. For example, there are something like 29 million abandoned oil wells in the world. Not only do they contaminate land around them if they are not properly contained, they leach massive amounts of methane. In the US alone annually, this leaks carbon into the atmosphere equivalent to 3 weeks of total oil consumption.

The problems of disused quarries are different. Properly managed they can become recreation resources for communities, or wildlife havens. There are some great examples in Norfolk, such as heathland in the old Leziate quarry outside King’s Lynn.

A short history of extraction

Extraction of the earth’s resources began thousands of years ago. The earliest pre-industrial societies grew on the basis of extraction – for example, flint in the stone age, metals in the iron age. But then, these materials were an aid to human survival and development on a manageable and local scale. Nevertheless, the technology they enabled, helped societies to grow in capability, and in productivity – and ultimately, in numbers. But for centuries the pattern and pace of life continued more or less on a continuum. Settlements clustered in villages, or towns by rivers and trading routes. Technology was still largely hand-tool based, or mechanical. Transport was powered by animals, wheels and wind.

Everything changed during the industrial developments from the early 19th century, for example with coal mining. It enabled power tools and machines to be driven at speed. Not only were more of the earth’s long-laid-down natural resources being extracted, but lifestyles changed dramatically around that industry. The scale of production grew to meet increased demand. And whole mining towns were developed for those workers.

Use of gas as a fuel technology began in the 18th century. Engineers in France and England developed and manufactured it chemically. They gasifyed coal etc in enclosed ovens, producing highly dangerous components such as hydrogen, methane, carbon monoxide and ethylene. The extraction of ‘natural’ gas is even more recent. In 2012, the United States used more gas than ever before in its history.

End of the oil age?

Although the first oil wells are known from 4th century China, mass development only began in the early 19th century. The most enormous and reckless extractions were to follow as oil technologies were developed. From the early 20th century, oil began to be used on a mass scale in heavy industries, for all transport by air, land and sea. For farming it has enabled a whole-sale re-organising of land management. But there has been enormous human cost in terms of drastic rural depopulation as people’s labour was replaced by machinery. From what we now know about the environmental consequences – for climate change – the future is going to have to be different. The end of the oil age may be in view.

Limits to growth

It is a truism that there are symbiotic relationships between the use of resources, the development of technology, and an increase in human prosperity. Ultimately population health and growth have continued through history, on the understanding that growth equals progress and is good. The change in view started in the 1970s with a realisation that there are limits to growth if the planet is to remain sustainable. But it ought to have been a more obvious that the earth does not prosper from the pattern of human economic expansion. Now we are starting to pay the true price for such exploitation. Extraction causes the earth’s impoverishment.

Extraction – extractivism

Humans have wielded relentless power to take from the earth. It is a daily almost thoughtless deed. The term extractivism describes the process of taking natural resources from the earth for the purpose of profit. Digging for treasure, mining for minerals, accumulating wealth. We are sympathetic to sustainable extraction, taking small amounts from one part of the world in order to make improvements in another. Thus we might regard turning rough stone into beautiful building facades, or clay minerals into talcum powder. But greedy over exploitation leading to ugly ruination, land and habitat loss for wildlife, that is what extractivism leads to, and that is what we must argue against.

Through our stone projects, our artists will demonstrate how creativity leads to resourcefulness and care for the environment.