15 July – 30 October 2016

Roger Ackling and Richard Long

Richard Long chose the title ‘Sunlight and Gravity’ for GroundWork Gallery’s inaugural exhibition, . It describes very clearly the forces which the two artists worked with – harnessing some of the most powerful forces of nature. It also suggests a mood. Gravity for seriousness, groundedness; sunlight for brightness, illumination. The inward pull of the earth from which we come, the grave to which we will descend; the light which gives us life, energy, hope.

Gravitation causes matter to coalesce and form shapes; sunlight is the burning force which both nourishes and destroys. Very sadly, Roger Ackling died in 2014. In his last year of life he had offered to make this exhibition to inaugurate GroundWork Gallery, and he suggested that Richard Long, his great friend, could be part of it.

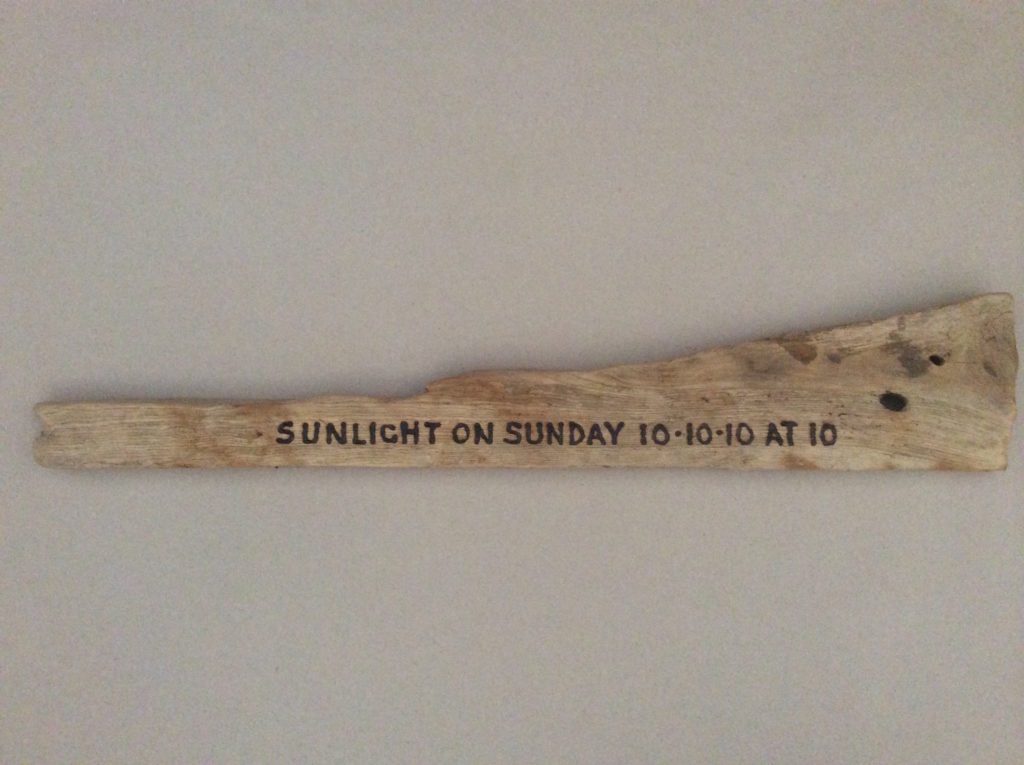

On show were some of the reliefs by Roger Ackling from the 1980s to the 2000s made with driftwood. Richard Long’s gravity works used soil and mud from Rivers Avon and Great Ouse.

All Roger Ackling’s works were loaned by his estate, which is now managed by Annely Juda Fine Art, London.

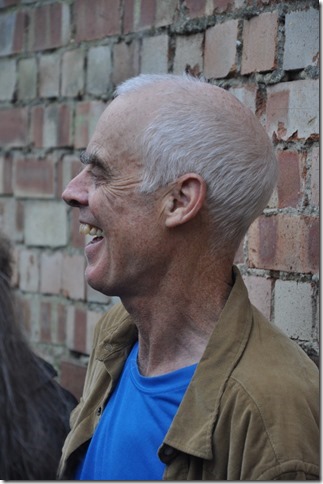

Roger Ackling

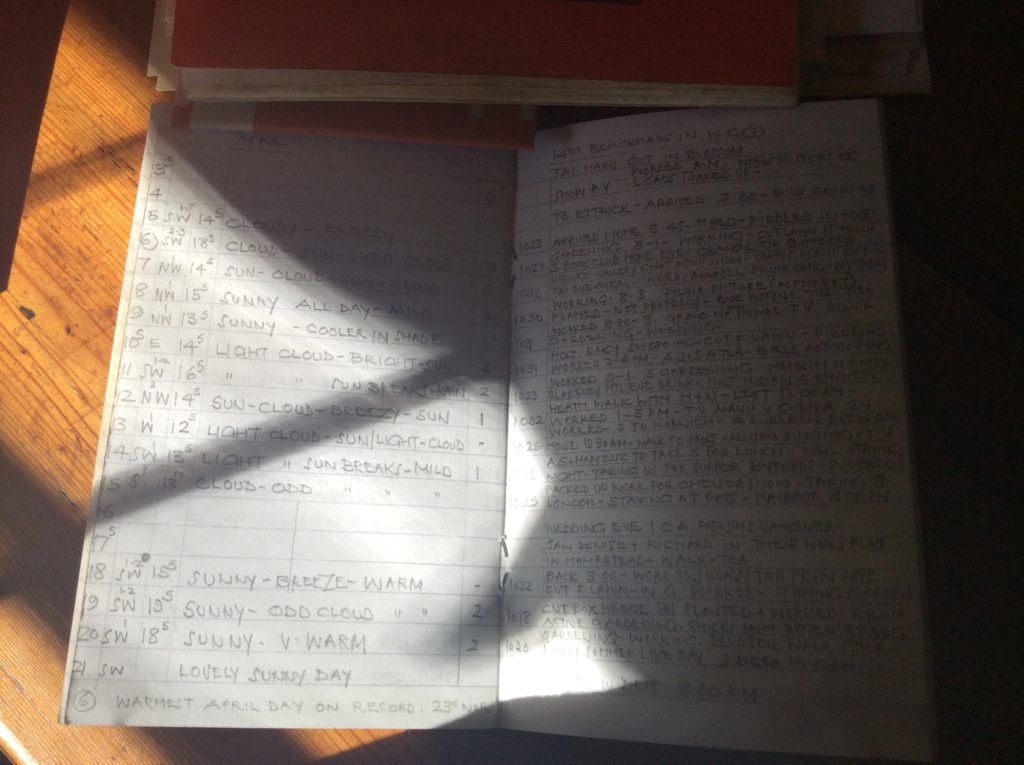

Roger agreed to this exhibition in the year before he died of motor neurone disease. and it became a a memorial tribute to him. He died at his home in Norfolk during its planning in 2014. Some of his unique weather diaries were on show for the first time.

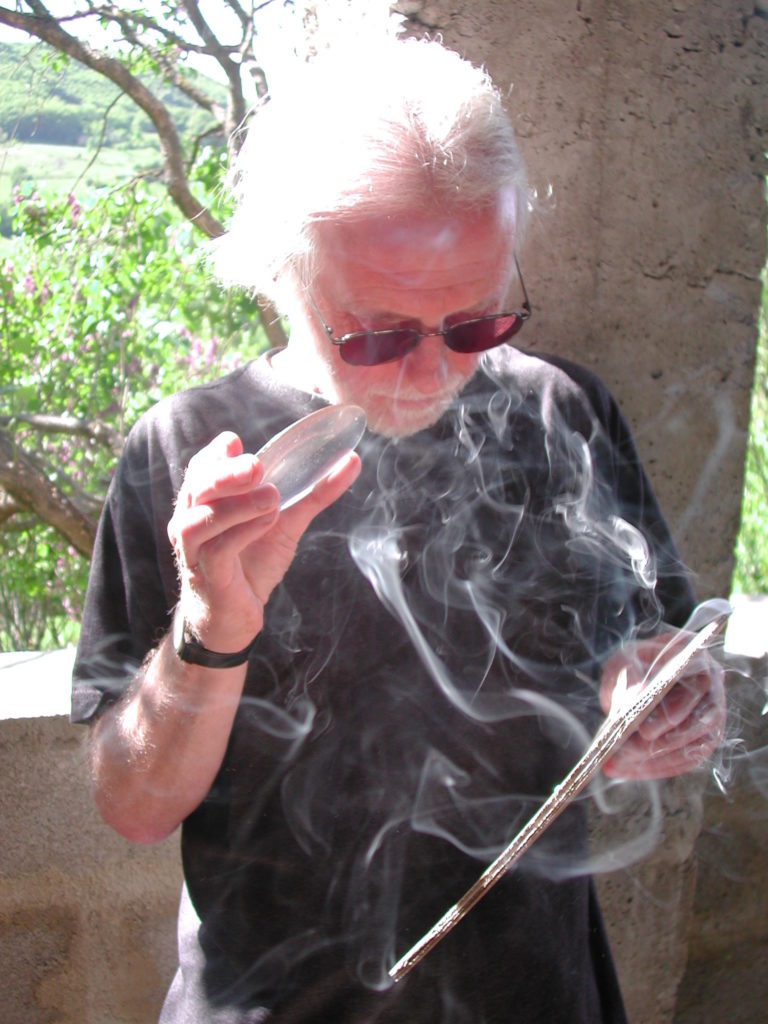

Sunlight on wood

Roger Ackling made many works at Voewood, Norfolk, where he lived, and in Scotland, where he also eventually had a home. Sunlight on wood with metal was his most usual chosen medium and he was a master at making beauty from almost nothing.

Roger made work by focusing a magnifying glass onto wood. When he could, he used driftwood found on the beach, but wherever it was from, it was always important that the wood had a history and signs of previous use. On each piece, he selected a precise area to re-work, and by directing his glass, he made regular marks along straight lines, painstakingly levelling, measuring, timing. His intervention is normally small in scale, packing enormous power and concentration into a tiny space.

Materiality of the earth, energy of the sun

In using the materiality of earth and the energy of the sun, both artists understood completely that they were in risky territory, making art from the elements: taking on the majesty of nature both as subject and as object. But it is more complex and less literal than that too. One can talk about how their work creates order and control, imposing upon it the random forces they encounter.

Chance balanced with precision

They balance chance with precision. Both artists seek their raw material assiduously in the landscape: vistas, paths, stones, rocks and mud in the case of Richard Long, and irregular and rough wood in the case of Roger Ackling. From it, each in his different way, uses refined skills of judgement, hand and eye, to create a world of regularity, rooted in the geometry, repetition and straight lines of modernism, but also exploiting the laws of physics.

Joint works

In 2006 Richard and Roger made an exhibition together for Roger’s New York gallery. They made joint works on the same pieces of wood. Richard marked his Avon driftwoods and sent them to Roger to add his marks, and Roger did likewise in reverse with his Norfolk driftwoods. Richard’s fingerprint stamps his human presence directly, marking his identity very firmly from the earth, whereas Roger continued with ethereal marks drawn down from the sky.

But the biggest differences in their work in general, are those of scale. Roger’s work was almost always intimate and modest, hand-held size and carefully controlled, focusing forces beyond the world. Richard’s are grand in scale, often gestural, using material from the ground.

The relationship between physicality of the work and its spiritual realm occupies both artists, but in different ways. For Roger it was about the act of making being both in the world and about being part of an essence of things.

‘Blank Thoughts: For my work to make no demands of awareness on the viewer; a kind of non-assertion. For the face of the work to be vulnerable, but not decipherable, to be open and closed, what Octavio Paz calls, ‘Towards a presence, towards absence and beyond’. ‘

Roger Ackling

Black sun

Japanese philosophy fascinated Roger, in particular the Japanese concept of Wabi-Sabi, applying to the beauty of imperfection, simplicity and transience, and in common with that, his work hints at a number of paradoxes and contradictions. The most obvious paradox was the fact that he made his black marks from the brightest sun. Several of his exhibitions were titled ‘Black Sun’.

These contrasts and paradoxes interested Roger. The opposites of dark and light. And parallels of enlightenment and mystery, knowing and not-knowing.

Nearness | feeling | Distancing – Nearness

Proximity | Distance | Nearness | Time | Space

Veiling | Revealing | Cherishing | Abandoning Holding | Realising

Placement within outer world | inner world’

‘Light from the sun

Darkness of line

Surface of object | Distance between lines

Veiling | Distancing

Shielding | Abandoning

He wanted his work to reflect these oppositions, not as fighting each other, but in co-existence. They were puzzling harmonies, a state of meaning and not meaning.

Roger was very sociable, yet his written words were nearly always private reflective ones, kept in a diary or delivered in lectures. He was a teacher, a great one, but not a public writer.

Richard Long

Richard on the other hand, writes his experiences in the public realm. For him, this is how his rituals are often explicit, there to ‘change the world’ in the variety of his text works.

Richard wrote that the gravity mud drawings in the exhibition are ‘not explicitly a dialogue with Roger, although in different ways and by chance we have both made work without physically touching the paper, or wood’.

The making of the framed Avon mud works has been about the act of repetition and an exercise in variation.

‘In my work I just activate nature, the natural force of gravity which makes the muddy water drain off the paper leaving a unique image. Besides the beauty of natural and unrepeating patterns, this cosmic variety is the idea of these works. They are all made in the same way, but are all completely different, which can be realised when seeing them in series.’

The Great Ouse River Drawing

He also made a new Great Ouse River drawing, with mud from the Great Ouse river which runs through King’s Lynn. The making of the work involves bravado, risk and skill. He gives himself a few moments to make it succeed, and once made, the work will not be redone. Twenty years of experience has enabled that to happen. The mud works last normally for a few weeks or months, then usually disappear at the end of an exhibition, to be painted over. Although (theoretically) they could last as long as a cave painting. For text about this work and a filmed interview with Richard Long see his artist pages here.

Proximity and distance

The artists have in common their solo practice. Neither has employed studio assistants, except perhaps to help with the occasional work involving print or digital technology. There is something ascetic about their privacy, the ritual involved in transforming the material using natural forces.

Roger said often, quoting a line in a Tarkovsky film, ‘rituals performed in private can change the face of the world’. For him, the time he began, the time it took, the time he finished, all these things were precise and significant. But so also were the unpredictable things, the conditions of the day, the environment, the light and shade, the wildlife, all were crucially important.

How does seeing their work help us to think differently? One is the idea of proximity and distance, near and far, what we can see but can’t touch, what helps us to see, but we can’t look at. The exhibition is about the top-down and the bottom up – the minutiae of the earth seen in the context of external control. It reminds us that we need to be attentive to both. But it also shows us how the everyday can become special. Materials and forces which are part of our very existence are made into art here. But the artists are also using carefully honed, but throwaway skills. There too is a paradox, showing us that every second matters and every fragment of earth needs to be nurtured and looked at more carefully.